The Math of Marriage

Celine Song’s Materialists and the math behind modern love.

Note: This post mentions some themes and a few early scenes from Materialists, but avoids major plot spoilers.

Materialists is a movie about how we assert our value to the world through marriage and material milestones. (It is also, crucially, a film that reminds us we must stop relegating Chris Evans to Netflix action movies with colors in the title and start putting him in projects where he can act with his face and not his biceps).1

It’s a movie, at points plainly said by its lead, about doing math: calculating someone’s value through how our life would look if we partnered with them, and quietly (loudly, if we’re talking Instagram anniversary posts) announcing our value by crossing the marriage finish line and by who’s standing at the end of it.

There’s a scene in which Lucy—a New York matchmaker in her mid-30s, the “eternal bachelorette”—tries to talk a client in a wedding dress with cold feet into walking down the aisle. The woman isn’t sure that, of all the things she could be in 2025, “bride” is the identity she wants to inhabit. (I relate to the complexity of this question. Nada Alic wrestles with “wife” in a piece for Harper’s Bazaar that made me laugh out loud and then stare into the abyss…my favorite genre).

Lucy asks her to be honest, even if the truth is ugly: why agree to marry him in the first place? After some hesitation, the woman admits that he’s handsome, has a good job, and is tall—traits that make her sister jealous, since her sister’s husband is less of all three. Lucy doesn’t flinch. I didn’t flinch. Actually, I laughed because I felt so affirmed. Lucy nods and replies: “So he makes you feel valuable?”

This scene, quieter, less dissected in the broader conversation around the film, feels like Materialists’ center of gravity, a clear signal that Celine Song is a writer first. The film unfolds like a thesis in motion: an idea being interrogated in real time, with each scene functioning as both question and evidence. But Song builds her argument not through words, structure, and syntax, but rather through texture: the soft grain reminiscent of 70s New York romances, every frame lit like golden hour or the perfect first date, the precision of three lived-in performances.

If this were an essay, somewhere it would read: How do we decide a person’s value? And how do we interpret our own by marrying them? But it is not an essay. It is a movie. This is an essay. So I get to ask.

It’s fascinating how marriage has evolved into the ultimate measure of worth; more definitive, even, than career, since finances often feed into marriage, but rarely the other way around.

I have to admit, I felt a smug satisfaction during the bride scene. Watching someone say the thing out loud—this isn’t about love, it’s about optics—felt like a neck crack after a decade of holding your head politely at a 40-degree angle for engagement season.

Any woman in her 30s will tell you: there’s a stretch of time when engagements start rolling in, prompting pressure on every couple in the periphery to hurry up and get engaged too, a sort of matrimony by contagion. The topic of conversation quickly becomes tinged with a slight competitiveness around how great you’re performing adulthood. The energy feels anxious and forced—like everyone got handed the same checklist at the same time and started sprinting. You can feel the intensity of these projections landing on you, even if you never asked for them, gently but insistently, like push notifications: this is where you should be, by the way, and there are deadlines. A collective rubric appears: one that no one explicitly agreed to, but that everyone seems to be grading themselves and everyone around them against. It’s wild how urgently people seem to want to wear khakis and discuss gazebo renovations with Gary from Accounting until they die—which, to me, feels like the inevitable conclusion of this checklist mentality.

A lot of it seems more motivated by social validation or a sense of superiority than by love or compatibility, as Lucy’s runaway bride admitted while I laughed with manic catharsis and was asked to leave the theater. Sometimes even by the spectacle of heteronormative domesticity: the Leave It To Beaver Checklist, as I like to call it. Superbowl plans, backyard upgrades and #CelebratingTheSmiths—markers far more apparent, tangible, and easy to get a pat on the back for than the actual, unphotogenic work of becoming a person. The uphill, cumbersome climb of self-discovery and self-esteem is easy to signal, but even easier to avoid, with Carrara countertops and a 4K flatscreen.2

Sidebar, but I think this is why people bristle at homeowners whose parents quietly covered the down payment (normie nepotism!). It’s not necessarily just jealousy, though it definitely can be. It's that homeownership signals discipline, good financial management, a well-paid career. Having a house is always nice but there’s a lot loaded in the identity of being a homeowner. Add in an unspoken family wire transfer, and the meaning shifts. The house still stands, but the symbolism crumbles. Again, it’s the material proof of having done the hard thing…without actually doing it. I personally celebrate any new location where I can sleep over in a guest room! And I also get why this type of fodder hits such a nerve.

But as the film asks: was marriage ever about love to begin with?

Lucy calls it “a business proposition.” What are you bringing to the table to negotiate a deal? This is how she justifies doing the math to calculate her clients’ compatibility. For men: height, salary, education. For women: BMI, age, beauty. And then come the hidden line items: Did you grow up poor? Are your parents still together, or did they scream across the kitchen for twenty years while you developed your frontal lobe? Even if you’re financially stable: is your job title sexy?3

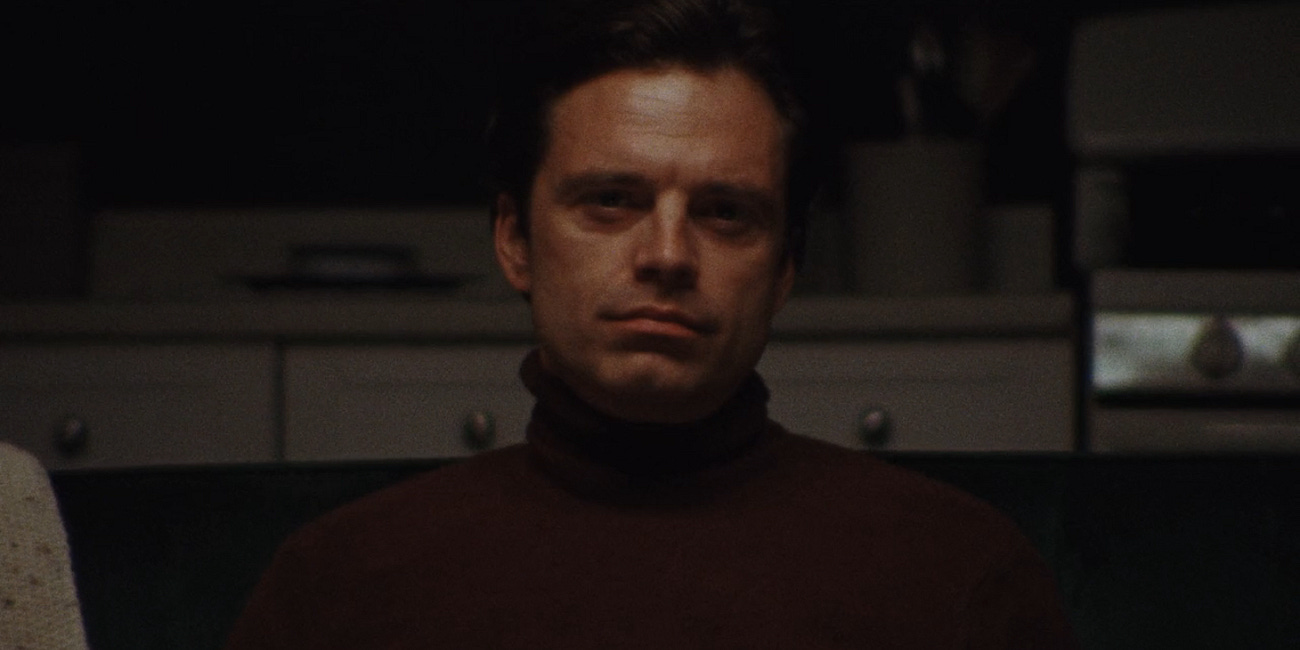

Song isolates these variables beautifully by making both men—starving artist John (Chris Evans) and “unicorn” Harry (Pedro Pascal)—equally charming, kind, and great as partners. There’s also no question of their seriousness about Lucy, which makes it easier to feel the emotional weight (or lack thereof) in each relationship. There’s a clean delineation: the two men represent opposite ends of the spectrum. One relationship feels effortlessly intimate—two people fully seen. The other feels like the LinkedIn-ification of love: an endless interview assessing whether someone is a good candidate for the job position.4

To be fair, there’s merit to the latter approach.

A lot of online content—specifically from Slavic women yelling at me about feminine energy (please, someone fix my algorithm, it knows I’m single in my late 30s!)—tells you to ignore chemistry (those are hormones!) and to be suspicious of attraction (those are fuckboys!) and instead focus on whether a man is a provider, a “good man” (still unclear on what exactly that means), and serious about you.

And there is sense to it. Constantly arguing about money has real potential to fracture a relationship. The logistics of survival can easily eclipse even the most immaculate vibes. Financial strain is, consistently, one of the top-cited reasons for divorce. Through a flashback, we learn it’s the very reason Lucy leaves John after a five-year relationship. Even if the final fight over eating at a good restaurant for their anniversary takes place in Times Square, where there are no such restaurants.

It also makes sense that most human beings would want to be with someone who has goals: a general sense of building something, and the discipline to work toward it. Where the wires get crossed among my Slavic sisters is in the lack of imagination. The commitment doesn’t have to be to work, or money, or the trad “husband role.” What if you met a guy committed to flying planes, or making chairs in a woodshop, or fermenting wine or something? It’s about passion. As John Paul Brammer puts it: “Passion fucks.”

Despite the beloved elements that have become Song’s signature—theater-like dialogue, long shots that ask the viewer to stretch their attention span, and a quiet intimacy that mirrors the slow movement of life—I can recognize where the film didn’t meet the expectations of what it was supposed to be. When I think about this mathematically, like Lucy, I can understand the critiques, especially when it comes to how the film was marketed as a rom-com. I can even see why it might not be considered a universally agreed-upon “good movie” in the way that unconventional romances like Phantom Thread, this summer’s Sinners, or even Song’s debut Past Lives are.

But I loved it anyway.

I loved how it made me feel. I loved that Song carried the same thesis—imperfectly, maybe, but tenderly—from start to finish. That, like many great writers, she gave voice to the questions so many of us have been circling but couldn’t articulate: Are we using marriage for love? For security? For performance? As a balm for the low-grade itch of existing in a life without clear instructions?

To me, the film’s answer to these questions is firm, if unsatisfying: sometimes, yes. But that doesn’t make us “bad.” It might just mean these institutions are constructed imperfectly and the trust we place in them is falsely weighed against the trust in ourselves. As Rachel Vorona Cote wrote about Haley Mlotek’s divorce memoir No Fault: “These readings register not as a collective indictment of conventional marriage—not exactly; instead, they illuminate, often queasily, our misplaced confidence in one institution’s capacity to facilitate the happiness of the masses.”

If we do less moralizing around the institution or timing of marriage, projecting our own anxieties on to others, we could reposition the concept as an individual choice with individual criteria and stop viewing it as material proof of success in life or worse, evidence we are lovable. Releasing the pressure would create far more blessed unions—which would make dating less of a competitive sport or a “number’s game,” sparing us from becoming Virgils in these particular circles of hell. It feels like a good time to mention that in Sweden, you get all the same legal benefits from being a “sambo” (a partner) as you do with marriage. Which means that somewhere out there, a Swedish couple is splitting a herring platter, feeling just as validated as the people who dropped 90 grand on a wedding in Martha’s Vineyard. Between this, the cheap candy bulk bins and Midsommar, they really have it figured out over there.

At some point, Lucy tells a client, “You are not a catch because you are not a fish”—and maybe that’s the point. Love, partnership, marriage—none of it needs to function as proof of anything. It’s not a verdict on your worth, just a choice you get to make, if you want to, on your own terms.

'A Different Man' is the Dark Comedy We All Need

There’s a specific kind of loneliness that comes from being certain of how others see you. Not from knowing, but from assuming—a private, miserable little conspiracy you’ve built against yourself.

David Lynch and the Allure of the Unexplainable

It was my first summer in Los Angeles, and nothing felt real. The palm trees stretched impossibly tall, slicing into a sky so flat and opaque it seemed painted, like a set piece. I hadn’t yet mastered parking on Echo Park’s vertical streets, posing for a party photographer without looking eager, or making sense of the city’s stran…

Knives Out! Sunshine! Snowpiercer! The Red Sea Diving Resort (despite the fact that this is, in fact, a Netflix action movie with a color in the title)! He is a very good actor! Give him to Denis Villeneuve or Luca Guadagnino or Ava DuVernay.

This is reminding me to rewatch one of the best movies ever written: American Beauty. If I ever had the opportunity to perform a Faustian bargain, I would wish to write like Alan Ball in exchange for my soul. Please alert any sea witches you know.

This struck me as an interesting contrast between LA and New York. In LA, the artist is often more desirable than the suit. Maybe it’s because, in LA, the artist has more earning potential through the dominant industry than an artist might in New York. If you remove money from the equation, most people would rather talk about Killers of the Flower Moon than mid-cap ETFs.

Why I struggle with Love Is Blind, but that’s an essay for another day!

Love this. The drink order was absolutely a paid product placement for coke and Budweiser

Chris Evans in a Luca Guadagnino - something I’d never considered but now that it’s been presented to me, I want it!